The opening paragraph of the section on the ‘Economy’ of the manifesto of one of the presidential candidates (for Nigeria’s general election 2023) says: “The structural model upon which our national economy has always been based needs major reform. Our economy is unhelpfully designed to export raw materials and import increasingly expensive finished products.”

This assertion, in all honesty, is rather faulty because it is focusing on the symptoms rather than the cause(s) of the ‘disease’; the high propensity for the importation of ‘expensive finished products’ is a function of the ready availability of ‘easy money’. And this availability of so much money (purchasing power) is rooted in the fact that the Nigerian economy has over the years been a victim of ‘Dutch Disease’—it has depended on one sector (crude oil) and huge revenue therefrom, and paid scant attention to other sectors.

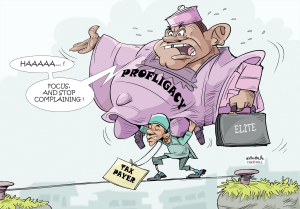

The upshot of this is that Nigeria has been awash with ‘Petrodollars’ and operated a ‘rentier economy’—one in which people schemed and positioned themselves to appropriate the flowing oil money without necessarily producing anything in the economy.

People pick and sell contract documents, for instance, (and ‘make’ money without any actual work); and the buyer of the documents sells to yet a third party—and everyone in the chain makes ‘huge profit’, and in most cases the contract is left undone. About the outset of this mentality in the early-to-mid seventies (1973-’76), the then military head of state was widely quoted as having said that the problem of Nigeria was not money but how to spend money. And this was the beginning of the mess in Nigeria’s public finance management!

It follows therefore that for any meaningful turnaround of the Nigerian economy to be achieved, the ‘petrodollar’ mentality and rentier lifestyle must be frontally and expeditiously addressed. This calls for a mind-set or psychological re-orientation to wean Nigerians off the ‘milk of easy money’ and the implied aversion to engaging in truly productive activity. No economy truly develops on rentier capitalism foundation; and Nigeria cannot be any exception. Incidentally, the hydrocarbon economy is already palpably endangered, especially in Nigeria where a multiplicity of endogenous and exogenous factors have become real threats.

The flow of the ‘petrodollar’ is seriously stymied, and almost quenching, but the ‘Dutch Disease’ that had held Nigeria down all these years, has badly permeated the nervous system of the Nigerian. Hardly do you have Nigerians who are mentally attuned to making a living in any other sector than the oil and gas enclave.

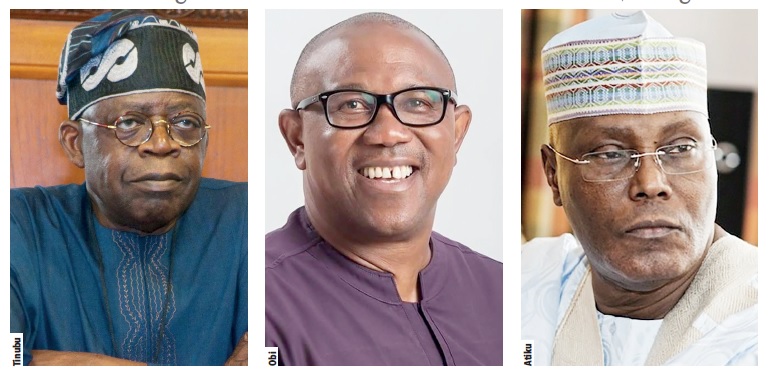

Unfortunately, up until now, successive governments in Nigeria have been making a mere singsong of economic diversification; paying only lip service to effective diversification of the economy. Now that the politicians have to come up with convincing manifestos in the march towards 2023 presidential elections, in what ways can they make agriculture meaningfully attractive and worthwhile to the Nigerian?

And particularly, how can agriculture, for instance, be made to attract and hold the attention of a jobless graduate (even of agricultural sciences), so that the society does not end up making him a scum? At this point, it is pertinent to recall that time there was when agriculture was the mainstay of the Nigerian economy. Was not the ‘petrodollar’ and its attendant rentier capitalism that ‘killed’ the sector and related activities?

It is not even enough that agriculture is made to create employment for millions of the unemployed, it should be prioritised and funded (ensuring mechanization, improved seed varieties and inputs, etc.) to tackle food insecurity and insufficiency.

At present, Nigeria is dangerously vulnerable to the vagaries of global food politics (shortages or scarcity) and disasters including droughts, flooding, etc. In the face of dwindling income, humongous sum in hard currency is still being expended on importation of all manner of food into Nigeria.

This reality is being worsened by numerous extant factors, including insecurity that has practically confined most agric practitioners to various internally displaced persons (IDPs) camps across the country. Not a few of these farmers are virtually marooned in their villages and hamlets, and hardly can safely go to their farms courtesy of insecurity. Any serious manifesto must convincingly show how to expeditiously and effectively ‘free the farmers’ to return to their jobs!

From another perspective, why have virtually all the solid mineral resources (including gold, diamond, tin, bauxite, coal, etc.) that have been discovered in commercial quantity been left unexplored over the years? Unarguably, almost every one of the 774 local government areas in the country is richly blessed with deposits of (solid) minerals. Why have these subnational governments (states) not been mining/producing these minerals?

Apparently through bad legislation, politics and fiscal policies, the states and local government areas have been made to live only on ‘sharing’ of oil money. Now, any meaningful economic manifesto must contain how to eliminate whatever impediments to (solid) mineral exploration and exploitation by the state governments. This ‘devolution of power and resources’ is fundamental to any strategy or initiative to economically prop the states to economic sustainability and buoyancy. It is a veritable channel to improving the much-talked-about internally generated revenue (IGR) of the states.

A lot of self-adulation by successive governments regarding infrastructural development of Nigeria has been going on; yet, the yawning deficit in infrastructural need of the country keeps widening. Indeed, if anything, it is essentially the very poor state of infrastructure in Nigeria that has rendered it uncompetitive as a business location. Name it, literally no manner of infrastructural facility in Nigeria is in a good functional state. Is it power infrastructure, aviation, road, railways, sea/air ports—all are at varying levels of decrepit state.

In a worst case scenario, Nigeria’s oil refineries have been abandoned for several years now, while the country imports almost one hundred percent of its refined products need. So, any manifesto that attempts to terminate the controversial fuel subsidy in Nigeria must realistically address the functionality of local refineries (both publicly and privately owned).

To the politician, it is easy to mouth the removal of fuel subsidy while campaigning, but the shame or irony of a major oil producer/exporter (Nigeria) importing all her fuel needs must be addressed from the roots. Arguably, it is the failings of governments over the years with the provision of critical infrastructure such as functional oil refineries, electricity power generating/distribution plants, railways, roads and seaports that have kept Nigeria at the bottom of the pyramid as regards ‘ease of doing business’ among the comity of nations.

How effectively and promptly these infrastructural weaknesses are addressed will determine the pace and shape of Nigeria’s economic recovery and development in the coming years. Unfortunately, all the presidential candidates, have in their manifestos, practically vacuous statements on how to perform this magic.

The implication of this is that it may take Nigeria much longer than thought to effectively become an economic force to reckon with, both at continental and global levels. With the poor ranking in ‘ease of doing business’ and other encumbrances, Nigeria can at best remain a large market, even as the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) plays out. Rather than attract and retain investors/businesses, the Nigerian environment of today scares and asphyxiates businesses. A good economic manifesto must address how to change this narrative. And it is a huge task.

•Okeke is an economist, sustainability expert and business strategy consultant.